Any intelligent fool can make things bigger, more complex, and more violent. It takes a touch of genius- and a lot of courage – to move in the opposite direction. E.F. Schumacher

Extreme violence has a way of preventing us from seeing the interests it serves. Naomi Klein

Evil turned out not to be a grand thing…It was selfishness and carelessness and waste. It was bad luck, incompetence, and stupidity. It was violence divorced from conscience or consequence. It was high ideals and low methods. Joe Abercrombie

Our age not only does not have a very sharp eye for the almost imperceptible intrusions of grace, it no longer has much feeling for the nature of the violences which precede and follow them. Flannery O’Connor

The tales of death were in their homes, their playgrounds, their schools; they were in the newspapers that they read; it was a part of the common frenzy — what was a life? It was nothing. It was the least sacred thing in existence and these boys were trained to this cruelty. Clarence Darrow

During what seemed to be a particularly gloomy week in New York and a particularly hectic week inside the UN, I found myself reflecting on some of the logistical and personal complexities and distractions of life that have consumed so many of the people I know and know about: The people forced to confront their own mortality or caring for others forced to confront the same. The family livelihoods hanging by a thread, drowning in paperwork and regulations that only the well-off can effectively manage. The endless drone of advertisers and others attempting to seduce us into purchases and activities we’ve forgotten we can neither handle nor afford.

And these are just some of the problems and stresses facing those of us who are relatively “well-off” in this increasingly unequal world.

More and more, our brains seem victimized by a conspiracy of sorts, a conspiracy too often “divorced from conscience or consequence,” a conspiracy to make our economic and social contexts seem more powerful, more complex and more violent than they need to be. In the name of some combination of status, comfort, thrill-seeking and self-interest, we continue to burden our own lives and make it harder on those who will come after us. We create messes that that we have been resigned in the past to merely mopping up after the fact, but which now gush rather than trickle, “spills” that now threaten to overwhelm both our increasingly distracted brains and the standard institutional capacities we’ve authorized to mitigate unwanted impacts.

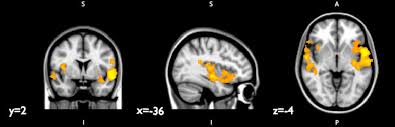

The UN this week took up a myriad of mostly-familiar, conflict-related messes from the Gaza and Afghanistan to Idlib (Syria) and the Central African Republic. All of these conflicts have “spilled over” for some time and represent places where UN and regional efforts to quell the violence have so far been only minimally successful. In sitting through these sessions and their seemingly endless “speechifying” (to quote the Dominican Republic), our thoughts extended to the people who have known little but conflict and violence in their lives, including the children who may not have experienced life on a consistent basis other than with homes, schools and medical facilities reduced to rubble, and with burials and explosions more prevalent than play dates. How have all these conflict-related stresses affected their brains? How have they impeded their collective capacity to contribute one day to building that elusive “sustainable peace” that we talk about endlessly in UN settings? How do we ramp up urgency to meet current security challenges given the diminished capacity that our violence, our distractions, our damaged politics and economics have inflicted on so many, young and old alike, worldwide?

Perhaps the best response to these problems in our recent hearing was articulated this week by the South Sudanese monitor and activist, Merekaje Lorna Nanjia, one of the speakers at an event on Security Sector Reform (SSR): Local Participation and Ownership of Reform Efforts, organized by South Africa on behalf of the Security Council Working Group on Conflict Prevention and Resolution in Africa. Nanjia urged the designers of SSR programs to “learn from their mistakes,” including their frequent insistence that Reform is only focused on “hard” security matters involving combatants and not also about the skills and capacities that more directly impact that ability of communities to cope with the threats and consequences of violence. She was one of several voices this week advocating for more attention to how violence diminishes human health and social possibility in myriad local settings. She reminded the audience that in promoting security, the value of social “inclusiveness” can hardly be overemphasized. And perhaps most important, she called for “demilitarization” that is in part about disarming those who create conditions of violence, but also in part about healing the minds of those for whom militarism has become the default standard for organizing daily life.

Slowly, thankfully, the UN is coming around to recognize that the damage inflicted on communities from armed violence is both pervasive and deep-rooted, and that effective SSR must accommodate the “mindset of citizens who have already had too much contact with militarized communities and instances of armed violence,” persons who have already had their capacities diminished and perhaps even their brains rewired through habitual trauma inflicted largely through the instruments of human conflict.

Ms. Nanjia was perhaps the most engaging speaker this week to raise the need for inclusive community involvement in security sector reform and conflict prevention initiatives. But there were other recent clues that we are becoming more systemically successful at carving spaces in our own brains for more thoughtful and people-centered responses to our security-related responsibilities. From the UN’s Rule of Law Unit urging both public dissemination of “basic information” about security and peace processes and more local agreements that can improve security in the shorter term, to the Former Ambassador of Fiji’s statement in the Treaty Body on the Law of the Sea advocating for greater attention to the “precautionary principle” in policy, there is a growing consensus regarding what one speaker noted at an African Refugees event this week, that we must learn to more effectively “tap into what makes us human.”

From discussions by force commanders on reshaping (and gender-mainstreaming) UN peacekeeping priorities to reflections on a Security Council resolution highlighting the needs of persons with disabilities in conflict situations, the UN this week demonstrated that it is slowly coming on board with the notion that the negative impacts of armed violence do not end when the guns are silenced; and that many of the assets to prevent violence, address its cerebral inflexibilities, and restore genuine hope for communities, are embedded in large measure within communities themselves. As Poland explained in the session on the Council resolution which it co-sponsored, “persons with disabilities are often forgotten in times of peace and are even more likely to be ignored during times of conflict.” Given this resolution there is now a framework for change on a human scale, as Poland noted, change that local communities and stakeholders are generally best suited to make.

This represents an important insight and the pace of its acceptance must accelerate. We simply cannot afford more security policy that ignores community, more security sector “reforms” that impede local participation, more violence that blocks out hope and possibility in local settings for the many who suffer its consequences. In this “frenzied” moment of our collective history when human cruelty seems to be finding its new level, we need the courage to take a collective deep breath, examine the “low methods” that too often accompany our high ideals, assess the interests that this current age largely services, and find new impetus for change within the communities that know best both their own people and what can most effectively heal their physical and emotional wounds.